the body as space for perception

September 2019

What brings the truth of the innermost to the surface most visibly? – The skin.

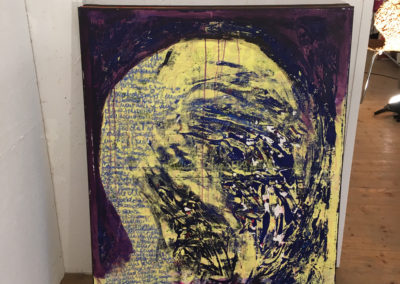

The skin is the sensory organ that develops earliest in human ontogenesis. It is our first contact with the outside world. Self and external perceptions arise through the skin, which in turn are subject to historical and cultural attributions and are constantly changing.

The skin – not only as a bio-physiological shell of the body – but with its stigmatizing, symbolic power implications is an essential part of my research area. I am concerned with the skin – which focuses on the sense of touch and the haptic system as a possibility of aesthetic perception.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel postulated in his Berlin lecture on aesthetics that the sensuality of art is only “limited to the two theoretical senses of face and hearing”, “while smell, taste

In my projects, on the other hand, I try to integrate all sensory perceptions, overlaying different forms of perception. Isn’t the highest goal of an artist to touch with his/her art? If this touching also includes an actual physical touch, the recipient is given the chance not only to grasp the work of art intellectually or

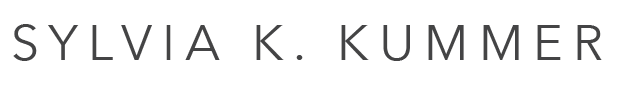

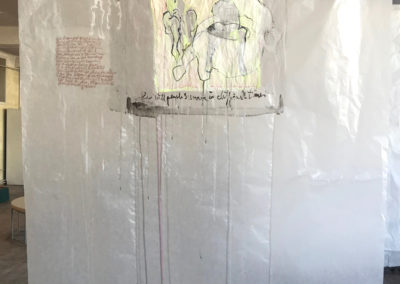

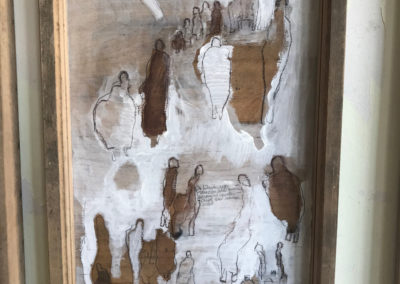

My objects are always „in motion“, „in change“, adapt to the context and the environment. They are individual elements, but also part of the whole. They can be seen and presented in two or three dimensions. This is important to me because our entire life is subject to a process of change.

Photo: Robert Proisl

Many and One

Christina Pawlowitsch

Sylvia Kummer: der körper als raum für wahrnehmung (the body as space for perception)

I CAME THE NIGHT before the opening|somewhat by mistake. I had read in a community paper that some months ago, two steps away from my home, in an old factory a new gallery had opened. The concept, the article said, was simple: young artists, right from the Angewandte or the Akademie (the two major art schools in Vienna). The rotation was quick so that every artist could be given a solo show. Every Thursday the new exhibition would open and be on display until the following Sunday. For the next year, the program was already complete, the article said.

That week was different though. Thursday evening, I walked into a deserted courtyard.

There was some light up to my left, on the second and last door of the long stretched building. I saw the silhouette of a person, who was, so it seemed, using the window board as a desk. Everything else was silent. I did not feel the presence of a crowd. A sign saying „Kunst ab Hinterhof“ („Art off back yard“) directed me to the far end of the building, into the back of the courtyard. I arrived at a door that was closed and so went back. Seeing again the silhouette at the window|obviously, someone working there on a computer|I decided to try that other, first, door. This was open.

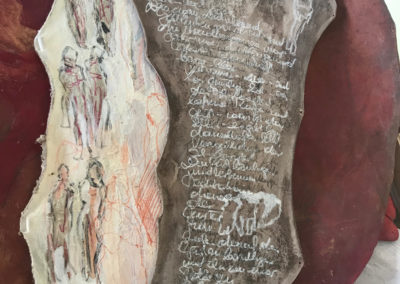

Stairs leading up. At the top of the stairs, a big silent screen. Next to it, the lettering of the gallery – „Die Schöne.“ I turned around to the big space where the light was coming from and came to understand that this was the exhibition, only that there was nobody|except the one person whose silhouette I had seen from below.

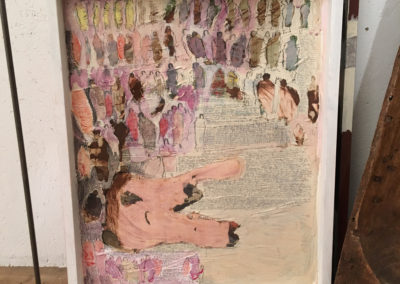

The space was enormous, wide and long. An immediate urge to dive into that space – the realm of these arranged objects, colors and light. An urge to become part of that space. As if you see water and want to swim.

It was a world with multiple communities or subcultures.

– It is multiple artists.

– No. She paused. It is all … my work.

It was the artist herself, Sylvia Kummer. She explained that the opening was the following day. I explained the misunderstanding that had brought me. I learned that she also had her studio there, right behind the exhibition space, on the same floor. Her show was somewhat off program, some kind of pop-up in the vicinity of her own space before Die Schöne would take up its regular program after the summer break.

It must have been the work of years. I forgot to ask the question. I realize in retrospect that I forgot to ask any question. But no questions were needed or urgent – because the work worked on me. That work was immediate.

It did not need any explanation.

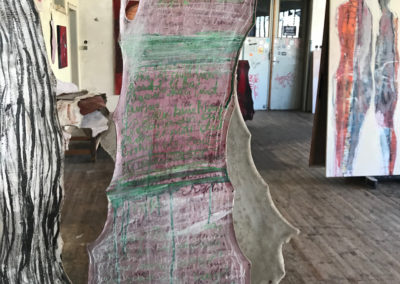

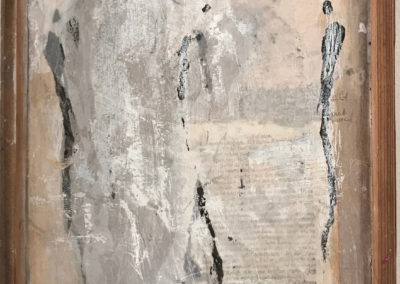

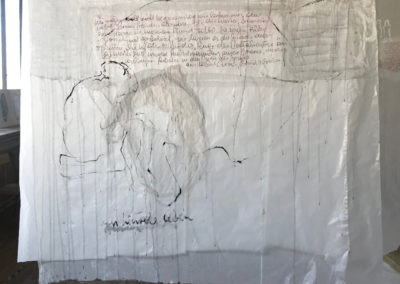

Movement – the body’s moving as a means to measures out the space that surrounds it, or to say it differently, that spans the space in which it comes to exist – is one of the themes that Kummer investigates. Another of Kummer’s concerns is the body’s surface – skin, the interface between the inside and the outside of the body.

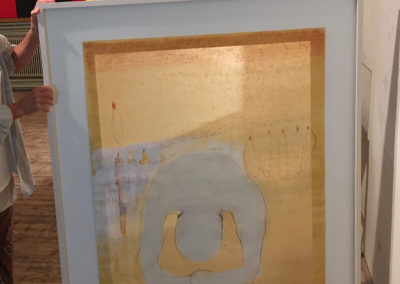

Kummer’s work is not complaisant. Still, the images and objects that she creates are terribly affectionate. I have no idea who –what – are these little creatures with antlers. But I feel curiously attracted to them. They evoke some kind of infant state of life|the beginning of movement, exploring and experience|not just in an individual’s life but of life in general, as if they were the memory of some earlier state of life engrained in our bodies.

der körper als raum fur wahrnehmung –

the body as space for perception – is not just about the body and its relation to space. It is work in and with the real space in which the exhibition takes place. As that it is many and one at the same time. There is one object of art that is the entire space. But then it is also multiple objects, many individual works: paintings, sculpture, groups of paintings and sculpture. That being one and many at the same time extends to the individual works. Many of the works have worlds in themselves: small paintings, drawings, or scripture within the bigger object.

Space, on the traditional view, has no intrinsic direction. There is, philosophers, say, no „metaphysical grain“ to any direction of space:

Instead, every spatial dimension is perfectly symmetrical. For another thing, space does not exhibit any movement or flow; unlike time, there is no dynamic aspect to the dimensions of space. And for a third thing, space is ontologically indiscriminate.It doesn’t matter whether you’re located right here or over there in space, since all spatial locations are equally real (John W. Carroll and Ned Markosian: An Introduction to Metaphysics, Cambridge University Press).

Time, on this view, is dynamic instead:

Each moment of time approaches inexorably from the future, enjoys its brief heyday in the spotlight of the present, and then ever after recedes serenely into the shadowy realm of the past.

Not only that, but your temporal location does matter, ontologically speaking: for the past is the domain of has-beens, and the future is a land of mere potential. Only the present is truly real (2010, 159. Ibid.).

„Wahrnehmung“ _ „perception,“ as my dictionary says – literally means something like „the taking of what is real.“ It has the connotation of „experience“ as well as „awareness“ and „coming to know“: The body, then, as space in which – by which – what is real is experienced and apprehended. That topic is not just articulated in the work exposed, but we as visitors are subjected to that experience in the very space in which the exhibition happens.

In that sense, „der körper als raum für wahrnehmung“ is also performance. And as that it becomes an exploration not only of space but also of time. For any real space exists only in time, and time passes. The one moment that made me feel that I wanted to dive into that space – in fact, that space as it existed then – is gone now.

This, of course, is a fundamental human experience: not just the fact that time passes but that we are aware of that passage. And from that awareness, probably, stems our attachment to objects – things tangible and real that become for us the embodiment of experience and the vanishing point of desires.

The one individual work of der körper als raum für wahrnehmung that exercised that force on me was one of the more traditional works. In fact, maybe the most traditional, and minimal, of the works: a figure bending over, crouching or in some other position close to the door, as if part of a movement, a dance. „Image de la peau“ was standing a part, on the top side of the space, right where you came to enter the space coming from the stairs – not so much isolated from the rest, but as if looking onto the rest: as if the opposing part, the one surface of reflection of all the rest. The piece has no intrinsic front and back side; it works both ways. It can be put in the middle of a space.

Depending on from which side you look at it, different details will become visible. Some of them, Kummer explains, will become visible only with time. Space and time then, again, within this one piece, are part of the investigation.

I would return to this painting the next day and then again three days later, Sunday late afternoon, before the show was taken down.

The space looked different then. The light had a different shade, and Kummer had allowed the visitors of the exhibition to move chairs and benches, which had broken up the tightly calculated tension between the objects.

The space had been inhabited then.

– It is such a pity that the show does not stay longer on display.

– Well, yes. In two hours I will take everything down. Tomorrow they move in with the show for next week.

Christina Pawlowitsch is assistant professor in applied mathematics at the University Pantheon-Assas in Paris.

Photos: Christina Pawlowitsch with permission of the artist.